Royce Pitchford

As Autumn comes to an end, some areas have now passed the mystical ‘ANZAC day break’. This then raises the questions, “What classifies as a late break? How likely is it? What risks are associated with my system and the time of break?” We decided to find out when the break usually happens and what we can learn from that.

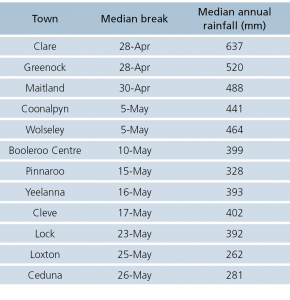

To determine the time of breaking rain we looked at data from multiple locations across South Australia. Data was taken from the Bureau of Meteorology and was from a period of about 70 to 110 years. We then calculated the median date of break which is the middle value of the total range of dates over the years.

Breaking rain was determined as the first 20mm or more rain event over 3 days since 1 April. This isn’t perfect - in some scenarios where a break consists of a few small rains it won’t show up. There are also some soil type differences, with heavier soil types often requiring more than 20mm to really wet up. But it still forms a good overall guide.

The resulting median time of breaking rain is the following:

This shows that the ‘average’ breaking rains occurring on ANZAC day isn’t true. ANZAC day breaking rains are more of an ideal situation than a normal one. The results also show a high correlation (78%) between the median annual rainfall and the median time of break.

There are many seasonal production risks that we don’t have control over but there are many factors that we do have control over through management. These include optimising sowing time to hit the ideal flowering window and carrying the right amount of stock through autumn. Knowing the normal time of break gives the information required to make these decisions. For example, budgeting on a median break of ANZAC day, in most areas, would result in feed gaps in most years. Keeping the right number of stock to match carrying capacity closes feed gaps before the break.

With an increase in information available, we can make calculated approaches towards risk management, rather than just guessing. Whilst the climate we’re working in could be changing, this data still provides value for perspective. Information doesn’t have to be from fancy bits of tech. Currently in agriculture, there is a lot of talk about the use of big data; this is often believed to be from sensors or other technologies. However, there is a lot of useful data that is already available. Easily accessible data sources such as BOM and CliMate provide good information on climate and weather conditions. In addition to this, we can get a better understanding of what is classed as good and poor conditions rather than calling anything after ANZAC day a late break.