‘Monsoons’ are the most prominent of the world’s weather systems, that traditionally bring a seasonal reversing wind along with rainfall. They are the winds that are caused by the temperature difference between a land mass and the adjacent ocean. These winds bring rainfalls during the summer in many countries across the world, thereby giving a start to their rainy season, which also marks the beginning of the agricultural or cropping season. Monsoons occur throughout the world, in parts of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, neighbouring regions of Arizona, California and Mexico, and also over here in northern Australia. However, the most important and awaited monsoon, from a grain marketing perspective, is the Asian monsoon, also called the Indian monsoon.

The Indian monsoon is a crucial weather phenomenon that significantly influences the agricultural patterns in China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri-Lanka. The monsoon plays a vital role in determining the agricultural productivity in these countries. The timing, distribution and intensity of monsoon rains directly impact the success of crops grown in these countries. A well-distributed and a timely monsoon is essential for a good harvest, while erratic or deficient monsoon rainfall can lead to droughts, crop failures and food shortages.

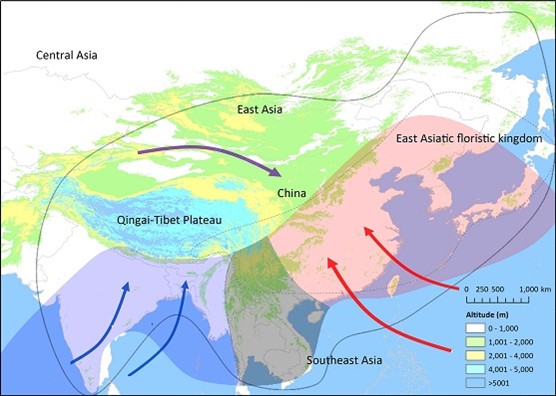

Image above shows how monsoon a traditional seasonal reversing wind accompanied by precipitation and rainfall brings a seasonal change to Southeast Asia countries.

Significance and agricultural dependence of Southeast Asian countries on the monsoon

Crop sowing and growth: A significant portion of the crops, especially rain-fed crops like wheat barley and lentils, rely on the timely arrival and distribution of monsoonal rains. Timely onset and distribution of monsoon rains are critical for proper crop sowing and growth. A delay or deficit in rainfall can lead to delayed sowing, affecting crop yields.

Water reservoir filling: The monsoon provides a substantial portion of Southeast Asia’s annual rainfall, replenishing water sources, rivers and reservoirs, which is vital for agriculture. Adequate monsoon rainfall is essential for filling reservoirs and water bodies, ensuring sufficient water availability for irrigation during the non-monsoon months, and helps in maintaining adequate soil moisture levels during the drier months.

Economic stability: A good monsoon season contributes to higher food production, which is essential for food security and the livelihoods of millions of people engaged in agriculture. With agriculture being a significant contributor to Southeast Asia’s GDP’s, the monsoon's impact on crop yields has broader economic implications, influencing overall economic stability and countries’ appetites for imports and exports. The performance of the monsoon has a direct impact on the agricultural output, influencing the overall economy. A good monsoon season typically leads to increased agricultural productivity and contributes to economic growth, whereas a bad or a delayed monsoon season may increase import dependency on crops.

Impact on global grain markets: The monsoon season is a lifeline for Southeast Asia’s crop production, which influences both agriculture and the economy. With high dependency on domestic crop production to feed its large populations, Southeast Asian countries rely heavily on rains brought by monsoons. Also, the monsoon season and rains affect the global agricultural markets as well. A timely and a good monsoon decreases demand from the consumptive regions, like India and China, and a weaker monsoon drives up the demand from these countries.

Not all of us know that both China and India are the largest producers of wheat globally. Their agricultural land area and the workforce involved in agriculture surpasses any other country. Both of these countries have large populations to feed and must keep optimum stocks of grains, specifically wheat, rice and lentils, for any unfavourable result of any geopolitical risk or climatic change event, both internationally and domestically.

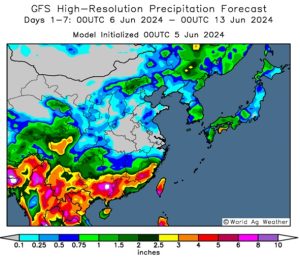

With these timely Asian monsoons, China could reap a larger, higher-quality wheat crop in 2024. This could weigh on reducing its wheat imports from countries like US, France & Australia, thereby affecting demand from China. If we look at the numbers, reportedly China has planted wheat on 24 million hectares for the year 2024. With a timely monsoon, China alone is forecasted to produce wheat above 120 million metric tons for the year 2024/2025 (considering average yield of 5mt/ha which is below their 10-year average of 5.9m/ha). If the Chinese demand gets curbed, the prices fall back, given the competitive nature of international trade.

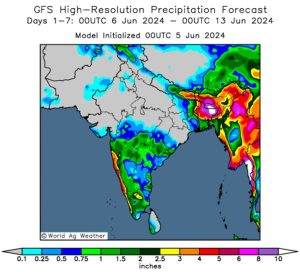

In India, the current outlook on the monsoon, for this year, is that it has pretty much arrived on time. With the timely arrival of the monsoon, one can assumingly say India might be expecting a good crop for the 2024/25 marketing year. A good monsoon in India, not only means a good autumn crop, but also helps in replenishing soil moisture for the winter wheat crop, especially wheat and barley that will be planted during the year end. The news that is being floating around, about India looking to import wheat by abolishing the import duties, may only come true if these monsoonal rains come out below average levels in next couple of months. But as we go forward, if these monsoons are consistent and widespread for optimum crop production in India, we might see India, not only getting self-sufficient, but also taking care of wheat demands arising out of Southeast Asian countries.

To summarise, from the grain marketing point of view, we all know that the prices are a reflection of supply and demand forecasts. Relatively, the international grain markets also keep a close eye on the monsoon data and pattern. The monsoon data helps them forecast the demand of crucial crops that might come from Southeast Asian countries and assists them by managing their books for demand, supply and pricing of grain going forward.

In the last couple of months, we saw Russian production of wheat forecasted for 2024/25 come back from 93 million metric tons to 80 million metric tons, just because of dry weather conditions. This drop in Russian production had a positive influence on the prices of wheat on CBOT, by almost 23%. Going forward this year, all eyes would be on the Asian/Indian monsoon data. If these monsoons bring enough rains to the Southeast Asian countries, we may see prices getting weaker because of lack of demand and falling imports from the Southeast Asian countries. On the contrary, if the Asian monsoons do not bring enough rain, then we may see a surge in imports of crops for the current marketing year, from countries like China and India. These imports may result in fulfilling their domestic demand for wheat and to control their domestic price inflation, thereby supporting the prices wheat globally.

The image above shows the Indian Monsoon season, which is right on time, thereby marking the beginning of the agricultural season.

The image above shows how good rains in China, brought by monsoons may promote sufficient crop production.

Rohit Lakhotia

Consultant, Commodity Risk Management

Pinion Advisory

Stay connected and stay supported with Pinion Grain Marketing

Whether you seek commodity risk management, grain consumer advice, or simply wish to chat, know that our doors are always open.

Contact the Pinion Grain Marketing team for more information

08 8525 3000

grain@pinionadvisory.com